Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy’s Consumer Pyramids Household Survey estimated a loss of over 10 million jobs in 2018. That was a big loss and there is no respite yet on this count. But a bigger loss on the jobs front is the loss of quality jobs.

Without getting into the gobbledygook of statisticians it is easy to notice the proliferation of tea and tobacco stalls, delivery boys, handymen, taxi drivers and the like. These are not jobs that educated people aspire for. At the same time, the availability of good jobs for engineers, MBAs and other post-graduate degree holders is not as prominent as it was about a decade ago.

IT companies and the financial markets are not as aggressive in hiring talent anymore as online and offline retail enterprises are in hiring labour to pack and deliver consumption goods. This shift in demand in favour of lower-skill labour implies that the premium for education in labour markets is declining.

A generation ago, it was inconceivable to get a job in the organised sectors without a graduation degree. This is no longer true. Today, the minimum education required to get a job in the organised sectors is much lower and is dropping.

Completion of graduation was not necessary for the BPO and call centre jobs, which were the fastest growing jobs in the early 2000s. In today’s fastest growing sector – the logistics industry – even higher secondary education is not necessary. These are jobs in the organised sectors.

Completion of graduation was not necessary for the BPO and call centre jobs, which were the fastest growing jobs in the early 2000s. In today’s fastest growing sector – the logistics industry – even higher secondary education is not necessary. These are jobs in the organised sectors.

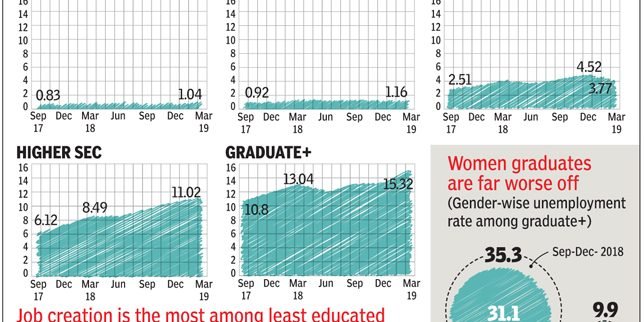

Jobs are growing faster at the lower end of the education spectrum and not as much at the higher end.

The Consumer Pyramids Household Survey quantifies the sharp fall in the rate of growth of jobs for the better educated in recent years. Over the last three years – between early 2016 and late 2018 – 38 million jobs were added for people who had completed only primary education, ie up to 5th standard. This implied that jobs for these barely educated people increased by nearly 45% over these three years.

In comparison, people who had acquired a little better education, ie between 6th and 9th standard, saw an addition of a much lesser 18 million jobs, implying also a lower 26% increase in jobs for these people.

The relationship between education and jobs gets worse as we go further up the education ladder. People who had completed secondary-to-higher secondary school education – 10th, 11th or 12th – saw a growth of 13 million jobs reflecting only a 12% growth over a three-year period.

Those with a graduate degree or a post-graduate degree saw the smallest growth in jobs between early 2016 and later 2018. These jobs grew by 2.9 million reflecting a growth of less than 6% over the three-year period.

Note that the growth rates of jobs keep halving as the education level rises – from 45% for the least educated to 26% for a small improvement, then 12% for secondary education and finally just 6% for the best educated.

The education composition of the employed is uninspiring. In late 2018, 55% or more than half of the employed workforce had not completed their 10th standard education.

If the quality of labour supply is nothing to be proud of, then the quality of jobs has to be correspondingly uninspiring. We see that while between 2016 and 2018 jobs have shrunk, the count of the self-employed has increased by nearly 20 million, which is a substantial 71% increase.

The self-employed are mostly those who could not find or retain a job during the age when most people begin their careers. After an age, when a person has no job offers on hand and when unemployment is not sustainable, then self-employment is the only option. Self-employment is rarely the preferred option at the beginning of a career.

In the past three years, this is the employment that has grown the most. There were 48 million self-employed people as of late 2018. Almost half of these emerged in the last three years – mostly in the form of small shops.

The self-employed include those who run small street stalls selling pan-beedi or pakora, etc, ferry goods on their hand-carts or boats, operate as insurance agents, brokers, etc. The better ones become taxi operators. Then, there are the freelancers like professional photographers, writers, who do gigs at their will. There is an entire range along the skills spectrum. Most of them are vulnerable.

The quality of work of most self-employed persons is so poor that they do not even consider themselves to be employed. Neither do the daily wage labourers or agricultural workers. Only statisticians and labour economists consider these vulnerable workers to be employed. This gap between the definition of the specialists and the perceptions of their subjects needs to be narrowed.

Measurement of human capital in terms of the quality of jobs is important. Also, human capital is not merely years of education. Till the potential available in education is translated into quality jobs it is useless. Jobs are human capital, not just education.

Source: TOI